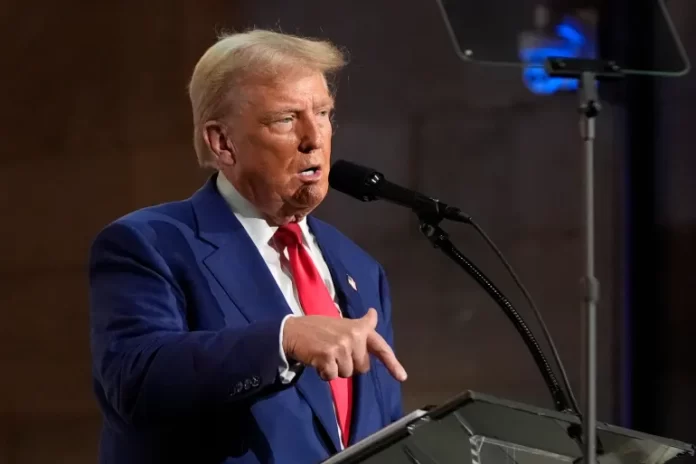

Concerns are mounting over the future of Nigeria’s economy following the recent imposition of a 14% tariff on Nigerian exports by U.S. President Donald Trump.

The announcement, made on April 2, 2025, has triggered fears among financial experts about the potential impact on the already fragile naira.

In a related observation, business and financial news platform, Bloomwiz, noted that Nigeria currently imposes a 27% tariff on goods from the United States—almost double the new tariff rate introduced by the Trump administration.

Commenting on the development, veteran journalist Ehichioya Ezomon warned that Nigeria may also feel the pressure of a value-added tax (VAT) penalty. Citing Trump’s remarks, Ezomon explained that the U.S. considers countries operating VAT systems to be engaging in practices comparable to tariffs, especially if those systems disadvantage American businesses.

President Trump had stated, “Countries using VAT—which can be more damaging than a tariff—will be treated similarly under our policy. Rerouting products through third-party countries to bypass this rule is unacceptable.”

He further noted that the U.S. has methods to quantify these hidden trade barriers, adding that countries wishing to avoid retaliation can simply lower or eliminate their own tariffs on American products.

Ezomon emphasized that Nigeria’s dependence on VAT for revenue could make the country vulnerable to further economic disruptions under this policy shift.

To assess the broader implications, Sunday Vanguard spoke with economic analyst Dr. Muda Yusuf, who is the Chief Executive Officer of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE). According to Yusuf, Nigeria’s trade exposure to the United States is relatively modest, accounting for roughly 10% of the country’s external trade.

“In 2024, Nigeria’s total exports were valued at $50.4 billion, with $5.7 billion worth of goods going to the U.S., mostly crude oil, natural gas, and fertilizers,” he said. “On the flip side, Nigeria’s imports from the U.S. include vehicles, wheat, and refined fuels.”

However, Yusuf noted that even with low direct exposure, Nigeria could still experience indirect fallout. He pointed out that the Trump administration’s recent actions signal an effective closure of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which once facilitated duty-free access for certain African goods into the U.S.

He also warned of inflationary pressure in the U.S. as a result of the tariff war, which could raise the cost of American goods imported into Nigeria. Additionally, disruptions in the global supply chain and potential volatility in crude oil prices could erode Nigeria’s foreign reserves and government revenue.

Another concern, Yusuf added, is that tighter U.S. monetary policy—prompted by domestic inflation—could lead to rising interest rates and capital outflows from emerging markets like Nigeria, thereby putting further pressure on the naira.

Despite the risks, Yusuf noted that there could be a silver lining. He suggested that as trade tensions escalate globally, new bilateral opportunities may open up for Nigeria with other countries affected by the U.S. tariffs.

Let me know if you want this rewritten for a specific format—e.g., newspaper article, blog post, radio script, etc.