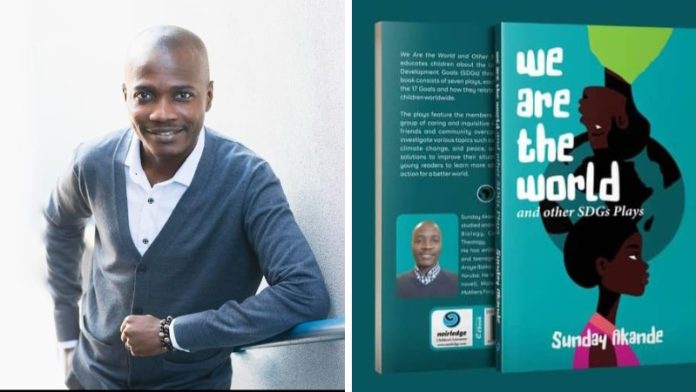

Berkeley-based Nigerian author, Sunday Akande, isn’t just a writer, he’s a mission-driven artist. A novelist, playwright, and poet, Akande uses his craft to tackle social issues and empower young people.

A prolific writer in both English and his native Yoruba, Akande has authored over 100 poems across three collections. His literary portfolio extends to novels like “Sorosoke” (2022) and “Water in the Basket” (2013), as well as the play “Mothers Forgive Fathers” (2015).

His latest work, “We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays” (Children’s Literature, 2024), is a testament to Akande’s commitment to social good.

In this interview with allnaijadiaspora, Akande dives into his new book and his life as an author with a cause. Excerpts:

Congratulations on your new book, We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays! It’s your 8th, what emotions does this milestone achievement evoke in you?

Thank you! We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays is my 8th book, having been actively writing for fifteen years. However, of all my books, this is the dearest to me, and that is because its manuscript stayed with me for 12 good years! So, I’m excited that it’s finally out. Not only that, but I also can’t wait to witness the positive influence that the book will undoubtedly exert in literary and scholarly circles, and most importantly, the value it will add to young people all over the world.

What sparked the initial idea for your new book, We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays?

The idea for We Are the World… came during my one-year mandatory National Youth Service in 2011-2012. The two-week orientation camp exposed me to the details of the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and I fell in love with the idea behind the whole goals. So, towards the end of my service year, I thought about telling stories around those goals in a way that children would understand and relate to. Then I wrote the first draft but couldn’t get it published. When the MDGs metamorphosed into the Sustainable Development Goals, I had to rewrite the manuscript to suit the present reality.

The idea behind the book is to expose younger ones to the contents of the SDGs and inculcate in them the moral value and responsibility to partner with their leaders in actualizing the dream behind the SDGs and thereby making our world a better and more secure place to live in.

What excites you most about sharing We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays with the world? What conversations do you hope it sparks with readers?

I’m most excited for the fact that this book will reawaken the world’s interest in pursuing the goals. The SDGs are meant to be pursued and actualized between 2015 and 2030, but many people, governments, and nations have forgotten about these important goals which should serve as a template for making our world less violent.

It should interest you to know why I chose to make it a children’s book. It is because, according to Mahatma Gandhi, a peaceful end must not be realized by violent means. Children exude peace, love, and empathy; they are thoughtful and selfless. Such a group should be our target with which the Sustainable Development Goals can be achieved. Now that they are young and innocent, these goals should form the basis upon which we build their loyalty to our world and every creature therein. We should start telling them stories that would spark their creativity for a more prosperous and more peaceful world – stories that unite a child in the remote village of Iyanfọwọrọgi with a child in San Francisco; stories that make every child around the world realize very early in life that they are stakeholders in this habitat of ours called Earth.

These and many more are the themes that my book portrays, and I believe it will elicit similar discussions from the public.

Your previous work tackled social issues, and We Are the World and Other SDGs Plays seem to follow suit. Why is this theme important to you as a writer?

Yeah, my works expressly deal with social issues. Well, I am an intentional writer who believes literary works are meant to heal society. I do this in three ways: I write satiric, prophetic, and didactic works, depending on my target audience. I believe that a writer doesn’t only entertain their audience, but they write from a realm superior to their material world to save their world from falling apart.

This is essential to me because every human being has the animalistic tendency to be disorderly; I believe writers are positioned at the rooftop to present an overview of our activities and laugh out or cry out loud if we are doing well or doing badly as the case may be.

Many readers connect with the characters. Was there a particular character in this book you found especially enjoyable or challenging to write?

Since I write serious works, my characters are expected to be serious. But if you’ve read any of my books, you’d realize that I have the funniest characters you’ve ever come across. And this is my attitude towards life.

In We Are the World, I have many interesting characters because it’s a collection of plays. These are vulnerable beings who do the unbelievable to rescue humanity from corruption; how wouldn’t you love such characters? From Olaniyi, a 10-year-old who wins a huge amount of money and decides to eradicate poverty in his community; to members of Book Lovers Club, children who meet to discuss reasons for truancy and decide to bring back their friends to school; to Salamotu, a woman who wants to divorce her husband because open defecation has led to the death of their children; to Ngozi who proves to her parents that girls are worthy of being sent to school. Great people!

However, I found it challenging to write about Yinka and Kingsley, who are youth corps members and one of whom sexually abuses female students and has unprotected sex with female corps members. Funny and sensitive story but I was careful not to pollute the minds of “my children”, the target readers. Thanks to Fatimah, a character who transforms that scene into a sex education class for her students and my audience. Of course, this shows the urgency for sex and sexuality education for our children.

Did you draw inspiration from any specific people or your own life experiences while creating the characters in the plays?

Oh, yes! I was once a child, and a very vulnerable one. My parents separated when I was only seven years or so. This exposed me to some sort of experience that could have had bad influence on my life. But in all of that, as retrospect, I remember that I was taken through a journey that also exposed me to creativity and weird ideas. As a child, I wanted to be many things, but I was limited by the decisions and actions of adults. If only we could closely examine the thoughts and ideas of young people!

So, what I did in these plays was to give a voice to a group of people whose voice we always neglect in our decision-making as a society. The characters are everybody’s alter ego. That makes the plays easily relatable to everyone.

Are there plans to see explored further, perhaps as a sequel or even in film or television?

Of course, I would like to explore film and television. All my works are rich in dialogue, and because I write about societal issues, film is a good medium to reach a wider audience. I want to start exploring with We Are the World. The writer of its foreword, Prof Labo Popoola, is the Director of the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network in Nigeria. He has called for the adoption of the book by the United Nations. I hope so, too. This would make the plays acted or staged, especially as children’s radio plays or soap operas, and be reproduced as books for school children in different languages across the world. That would also be a template for the next phase of the goals as the present SDGs are expected to last till 2030.

When did your fascination with words begin? Tell us a bit about your childhood experiences with literature.

Africa has a beautiful oral tradition, so I grew up in a community where folktales, legends, dance, and drama were upheld.

I’m a natural storyteller. As a young boy, my friends preferred that I watch a movie, for instance, and narrate it to them rather than watching it themselves. I lived in a not-well-educated environment where old people needed someone like me to help them write letters to their children abroad. While doing this as young as eight, I listened to their stories and, over time, perfected the art of crafting stories, some of which were emotional.

In primary five, I was co-opted into my school’s drama club, and I acted a radio play. When I got to high school, it was easy for me to be a pioneer member of the drama club, press club, and debating society. I had to write short plays for the drama club weekly, in addition to the articles I wrote for the Press club. I also had a passion for languages, even though I was in science class.

Some African literary works also added to my passion for words. I read almost all the D.O. Fagunwa’s classics. I read Buchi Emecheta, Amos Tutuola, Isidore Okpewho, Chinua Achebe, and Wole Soyinka.

Can you share a glimpse into your creative process? How do you develop ideas for your work?

I write every day. Writing is the major thing I do. But the way I do it is what I may not be able to explain. I don’t have a pattern for it. For instance, the kind of environment wherein I write varies per time. The most important thing is that I make sure that I create the atmosphere, depending on the inspiration. Sometimes, I want to write in a noisy environment, while some other times, I want it silent.

How do I get the inspiration itself? Three ways: one, a voice dictates to me on few occasions; two, nature suggests to me most times; three, my mind often takes me to where I no know, and I just follow it like mumu (laughs). When the ideas come, I either write them down or save them in my memory until they’re ripe to be told through the right medium.

What role do you believe reading plays in our lives? What are you currently reading yourself (plays or otherwise)?

Reading is the fuel that powers destinies; it is the light that brightens people’s paths in life. If a man would go far in life, he needs to do two basic things: open the pages of books and open the gates of cities. Those are the two places where treasures are hidden. You are as bright as the books you read. When we read, we commune with superior minds; this is because writers operate at a realm higher than themselves. So, when we read their books, we engage with their world, their thoughts, and their ideas. That transforms us from our crude, local state into a refined, polished, and global state.

I read plays. You see, our elders say, “When an eye makes pus, we remove the pus and show it to the eye.” That’s exactly what a play does – it shows us what we do, how we do it, and the consequences of what we do. It makes us do a recapitulatory exercise and see who we are in and out.

Works of art generally are meant to be interpreted by the audience; that’s why a literary work may have diverse interpretations. However, some plays tend to lead the thoughts of the audience by interpreting the contents. Plays are more real because the characters are livelier. So, plays can influence the audience faster than any other genre. They can easily shape every aspect of our culture, be it language, dress, food, music, or spirituality.

But I’m not currently reading plays. I’m now a doctoral student working on how to transform violence among young people. I’m reading lots of books on victims and perpetrators of violence. I’m reading about trauma. I’m reading about theories and ethics of nonviolence and peace-making. All these will eventually translate into more literary works from me. I will be using writing as a tool for peace-making in our world.

For aspiring writers, what advice would you offer on crafting compelling stories and achieving publication?

Publishing a book goes beyond writing compelling stories. It is an art you must understand. While it often takes one person to write, it takes several professionals to get it published. Now, as a young writer, don’t let the idea of wanting to be read by all means make you waste your stories, energy, money, and time. The most important aspect of writing is getting the right publishers to work with. The right publishers know how to get your book published and make sure it gets into the hands of your target audience. That is very essential; otherwise, you would be the only one reading your compelling stories.

Your previous work was featured at the 24th LABAF, and you met Nobel laureate Prof. Wole Soyinka! How did this experience influence you?

The 24th Lagos Books and Arts Festival was my first and it was a turnaround for my writing career. My book, Sorosoke, was featured as one of the books of the festival and the acceptance was overwhelming. My book was unofficially named the best book of the festival in terms of its relevance to the theme of the festival, “Pathways to the Future”. I was able to meet the “movers and shakers” of the Nigerian arts and literary world – writers, artists, filmmakers, journalists, actors, publishers, musicians, etc.

They all loved my book and they all had one message for me: “Please, don’t stop writing.” When I met Professor Wole Soyinka, he thanked me for writing such a book. One of his goddaughters hugged me and said, “Here’s a book Soyinka would have written when he was your age.” To me, that was not only a compliment, but it was also an invitation to the hall of great writers. I was glad, and that experience keeps challenging me to write more.

How is your recent relocation to the US influencing your writing? How does the American literary scene compare to Nigeria’s?

Well, the American culture is different from the African culture, and so does their literary scene. We have an oral tradition in Africa as against the writing and reading culture here in the US. Everywhere you turn to here, you see people reading, young and old, male, and female, on streets, in transit. People are reading. This makes literary work a successful endeavour here. Writers are eager to write more because readers are waiting to consume their works.

I live in California, the home of Hollywood. So, I know the kind of attention and investment that go into literature in the US. They know that literature preserves and shapes culture, which in turn shapes society. Writers and filmmakers, for instance, influence policymaking, inventions, and governance here. They see ahead and suggest things to their government. And they are taken seriously!

So, more than ever before, I see myself not just as a writer, but also as a major stakeholder whose words are important for direction.

What do you miss most as a Nigerian living abroad?

I miss the warm weather. Nigeria has the weather that makes you “feel at home.” You can remove your clothes and sleep. Here in the US, you cannot feel at home even in your home. (Laughs). Even though I live in a state with relatively fair weather, I still miss the Nigerian weather. I can’t wait for summer. (Laughs).